Whenever a company publishes a PEA, Pre-Feasibility Study or Feasibility Study, there are a few parameters we immediately focus on. Besides the used commodity prices and (overly) aggressive cost inputs, there’s one major factor which could kill a project: the Discount Rate used in the NPV calculations.

About discount rates and their impact on NPV’s

Just to refresh your memory; a discount rate is a percentage which is used to discount the annual cash flows. Using a discount rate of 10% simply means the cash flows get divided by 1.10 in year 1, by 1.10² (1.21) in year 2, and so on. That’s also why companies are trying to maximize the cash flows in the first few years of the mine life as the later in the mine life these cash flows are being generated, the lower the impact on the Net Present Value.

Perhaps an example could make this clear.

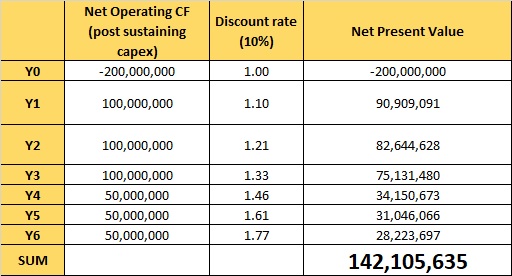

Project X has an initial capex of $200M, and will generate $100M per year in Y1-3, and $50M per year in Y4-6 of the mine life. On an undiscounted basis, the sum of the cash flows would be $450M – $200M = $250M. On a discounted basis (10%), the calculation will look like this:

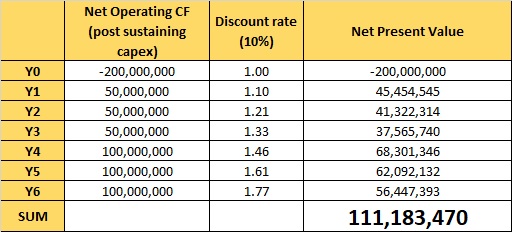

But what if Project X would have a different cash flow schedule? What if it would generate $50M per year in the first 3 years, followed by $100M per year in the next 3 years?

Indeed. As the previous images shows, generating less cash flow in the first years of the mine life has a huge impact on the project’s NPV.

So although the undiscounted sum of the cash flows remains the same $250M, it’s very clear the discount rate has a huge impact on the Net Present Values. And that’s exactly why companies are trying to get away with using a discount rate as low as possible when they present their economic studies.

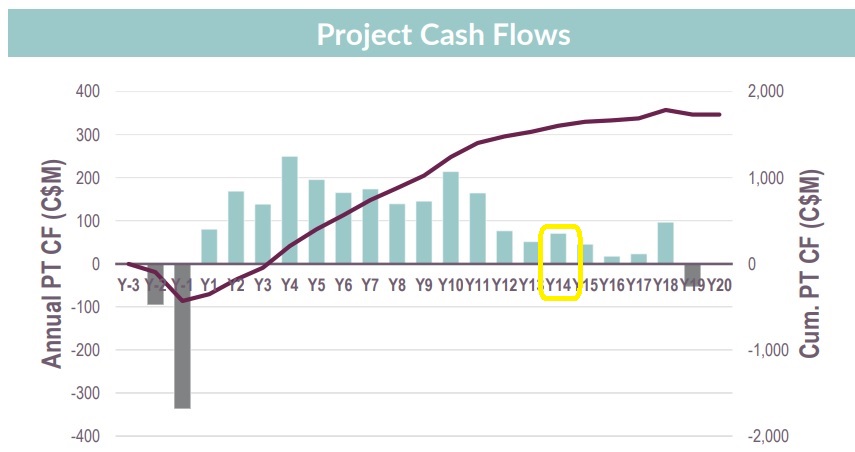

An excellent (and recent) example of the importance of ‘front-loading’ your incoming cash flows is provided by Fireweed Zinc’s (FWZ.V) Preliminary Economic Assessment. Although the technical report hasn’t been filed yet, this image from the company’s updated corporate presentation shows the first 11 years of the mine life are the main reason why a C$448M NPV was possible. The final 7 years of the mine life won’t provide any meaningful (if any) contributions to the NPV (which was calculated using an 8% discount rate). For instance, the C$60M (visual interpretation) that will be generated in Y14 will be discounted by a factor of 2.94 (1.08^14), contributing just C$20M to the overall NPV. And the C$100M in Y18 will be discounted by a factor of 4, resulting in an NPV contribution of less than C$25M.

So a total gross value of C$160M in undiscounted cash flow late in the mine life contributes less than C$45M to the C$448M Net Present Value of the MacMillan Pass project.

But how should an appropriate discount rate be determined?

Technically, the discount rate is based on the risk-free interest rate, increased by a ‘mark-up’ based on the risk factor. This risk factor depends on a lot of parameters, but the geopolitical situation at the project is undoubtedly the most important one. That’s why a project in the DRC should always, really ALWAYS use a (much) higher discount rate than a project in Nevada or Québec.

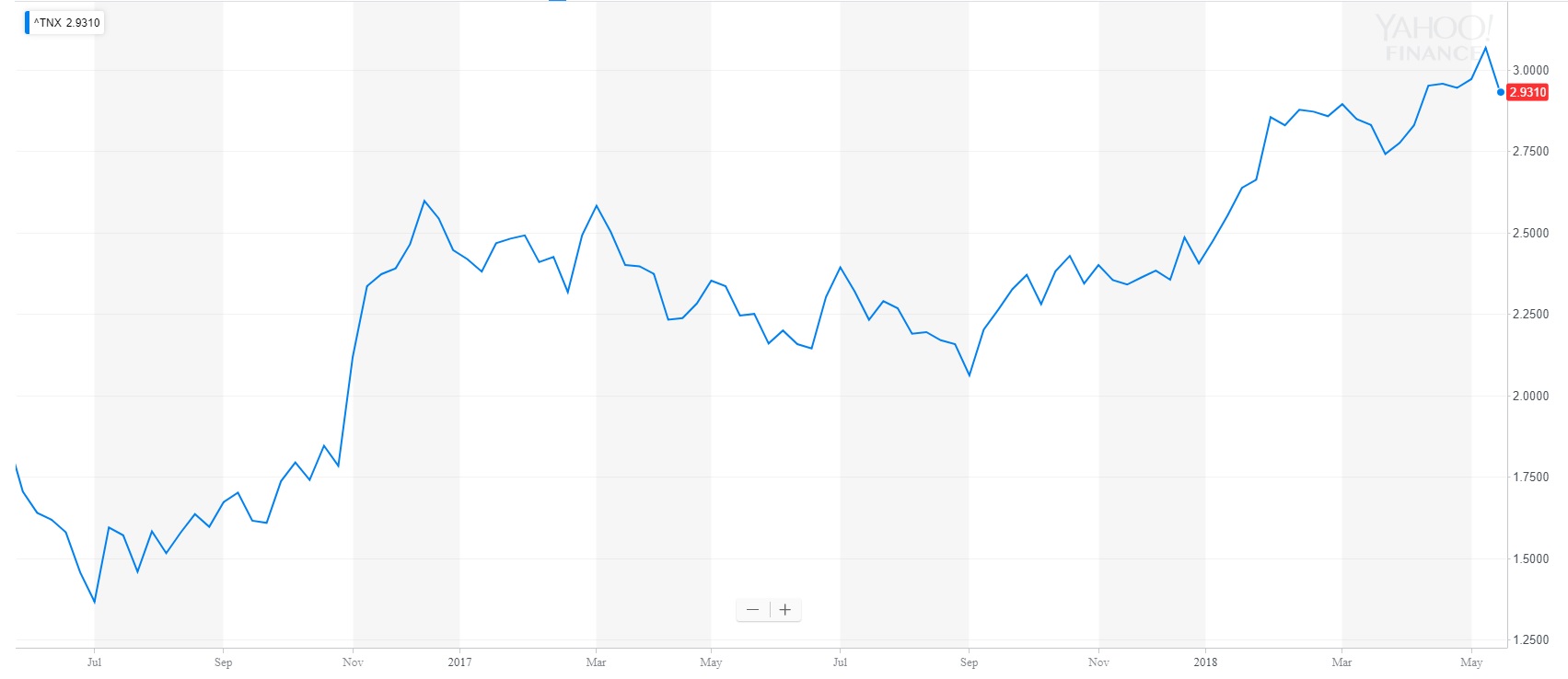

And what about the risk-free interest rate? There are no free lunches and there are always risks involved in the financial sector. But we think it’s generally accepted to use the 10 year government bond yield of the country where the project is located. With a 10 year bond yield in the USA of 2.93% and a 10 year yield in Canada of 2.35%, it’s clear the discount rates used in the NPV calculations should be substantially higher than the 5% we see quite often these days.

10Y US bond yield, source: Yahoo Finance

Let’s put this in perspective. Do you feel a mark-up of 2.07% over the US treasury yield is a high enough mark-up? The eternal debate about bonds and hard assets aside, would you prefer 3% from a government that has never defaulted on its obligations? Or would you be willing to take on the permitting, financing and execution risks associated with a mining project for an additional 2% in risk compensation?

Exactly. Discount rates should fluctuate with the underlying (perceived) risk-free interest rates. And even companies that undoubtedly mean it well are falling for this trap. Roxgold (ROXG.TO) is operating a gold mine in Burkina Faso and has done a remarkably good job in getting the project up and running. Kudos for the entire management and technical team. But we were flabbergasted to see how Roxgold used a discount rate of 5%. It’s a great team and a good project.

But a 5% discount rate for an African project? That’s a tough sell.

The cost of debt is increasing to levels way higher than the discount rates used in economic studies

And you don’t have to blindly believe us when the risk-related mark-ups are increasing. Here’s a genuine question.

Who deserves the highest risk-related mark-up? A secured lender, or a shareholder? It’s absolutely undeniable the cost of capital is much higher for equity than for debt. Although lenders are much more certain about getting repaid, they demand a (much) higher risk premium for providing capital (which is usually secured against the assets of the company). In the next table, we are providing the data from three recently announced financing deals (as well as an older deal for Lydian International). In all deals, the lenders are requiring a substantially higher risk premium for their secured debt, than the discount rate used in the respective economic studies.

The table speaks for itself. And just to single McEwen Mining out. Is it fair to use a 5% discount rate to calculate the Net Present Value of a project when a senior secured lender requires 9.75% for a 3-year bond? Or perhaps Harte Gold. Why would shareholders be satisfied with a discount rate of 5% if a senior secured lender gets almost twice as much for taking less risk? In Harte’s case, the 5% discount rate implies a 2.65% risk premium. But the lenders required a 7.47% risk premium despite the more senior status of their investment.

Of course, this isn’t a pure black-white situation. Shareholders can participate in the upside should companies find and mine additional resources, or if the underlying commodity prices increase. Debt investors will only receive the contractually agreed interest rates, ‘limiting’ their returns, but these also protect them from decreasing commodity prices.

But that’s not the main point here. The main point is that by using low discount rates with low risk-related mark-ups, the NPV calculations are overly optimistic as even lenders with a more limited exposure to the project are requiring much higher risk premiums for the risks they are taking on.

Conclusion

We think it might be time to re-consider alternatives for the discount rates used in the NPV calculation of projects. We think it’s pretty clear the era of 5% discount rates is over, as this represents a mark-up of just 2% over the risk-free interest rates. Companies should no longer be able to get away with 5% discount rates.

We see three potential options.

First of all, the used discount rate could be based on the average cost of debt. After all, if (secured) lenders require a mark-up of 6-9% over the risk-free interest rate, there’s no good reason why the NPV attributable to the equity holders of a company should be based on a lower mark-up. The downside of this solution obviously is the fact the real cost of debt will only be known after the final feasibility studies have been completed as those are generally used in financing discussions.

Secondly, perhaps a sliding discount rate could provide a solution. Whereas the initial risks can be well-interpreted for the first years of the mine life, nobody has a crystal ball, and nobody knows what will happen in 10 or 15 years from now. Countries that are perceived to be safe could suddenly pull weird tricks and become riskier investment destinations (think about the evolution of Indonesia, where Freeport McMoRan (FCX) has been fighting to retain control of its Grasberg project). Using a higher discount rate in the later phase of a project could be a first step to take the increasing uncertainty into consideration.

A third option could be to borrow a ‘standard’ discount rate from the oil and gas sector. Every single oil and gas producer publishes its PV-values with a standard 10% discount rate. Some companies do provide a sensitivity analysis including 0%, 5%, 15% and 20% discount rates, and that’s fine. But there’s one uniform discount rate throughout the sector. 10%.

We admit there’s no perfect solution for this issue. But the era of companies getting away with using a 5% discount rate should be over.

If anything, we hope we provided some food for thought here.

The author has a long position in Fireweed Zinc, but no position in any other company mentioned. Please read the disclaimer