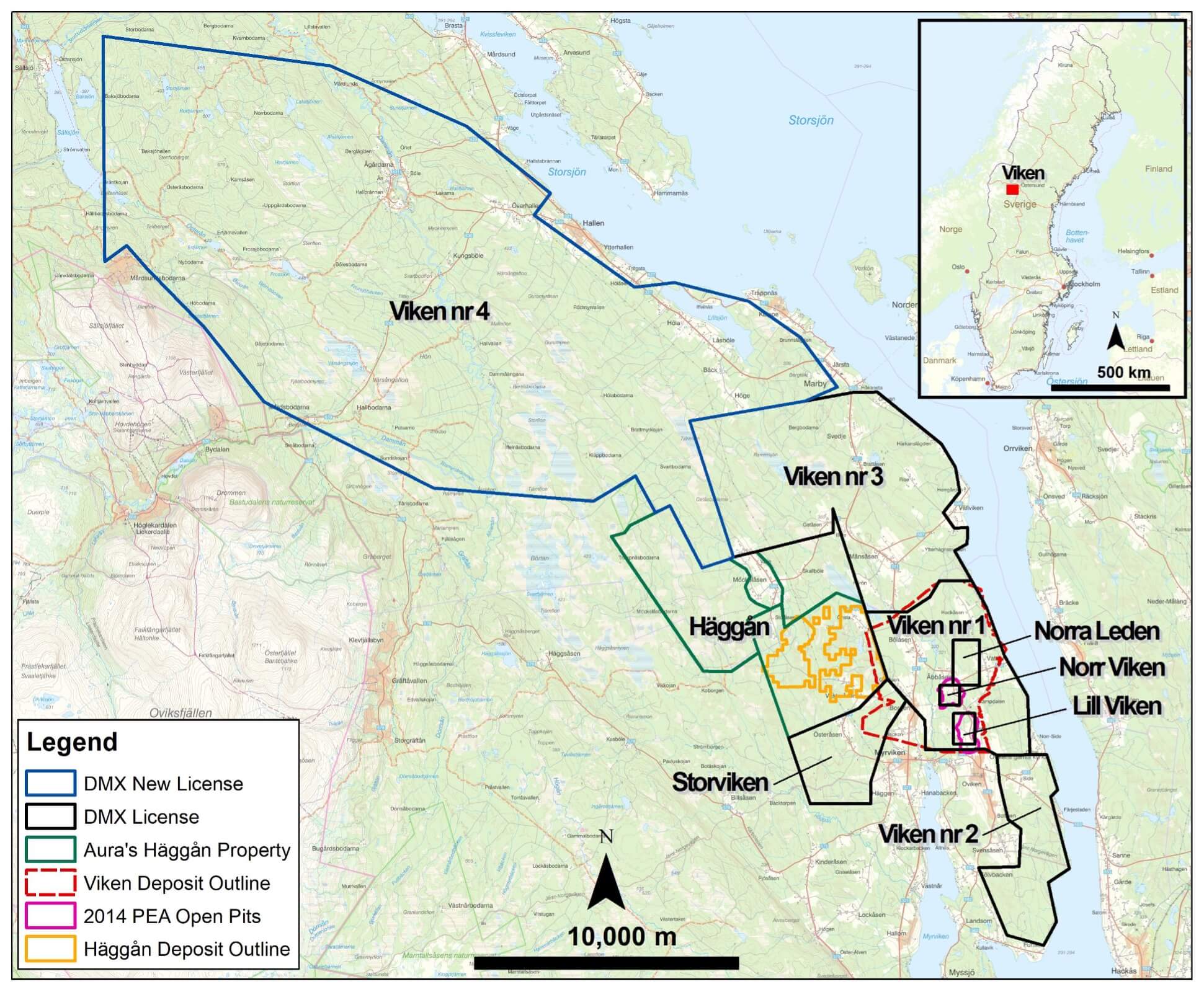

We attended the Nordic Funds & Mines conference in Stockholm last month, and that was an ideal excuse to join District Metals (DMX.V) on the site visit tour and visit the Viken flagship property. As you remember, about a year ago, District Metals changed its strategy as it learned the majority of the Viken uranium-polymetallic deposit could be staked for a four-digit cash payment. Subsequent to the initial staking of the majority of the asset, it acquired the remaining interest from a third party, allowing District to consolidate 100% ownership of the Viken deposit.

Right now, there is a ban on mining and processing uranium in Sweden. This makes the Viken deposit virtually worthless (of course, the other metals could be mined without recovering the uranium but that Isn’t really the company’s ‘Plan A’), but the wind is changing direction in Sweden. After decades of opposing (new) nuclear energy and the mining and processing of uranium, the current Swedish government appears to be paving the way to lift the uranium moratorium in the near future. It’s our understanding the final details are currently negotiated away from the spotlights and the tv cameras, but pretty much everyone we talked to in Sweden was adamant: the moratorium will get lifted.

This essentially makes District Metals a binary bet on whether or not the moratorium will get lifted. Sure, District still has the joint venture with local major mining company Boliden (which has absolutely nothing to do with District’s uranium division) but the Viken project is the main driver of the current valuation.

Visiting the Viken deposit – easier access than expected

It was surprisingly easy to travel to the Viken project. There are multiple flights per day between Stockholm and Östersund, the capital of the Jämtland region. The region itself is very sparsely populated and close to have of the inhabitants live in the greater Östersund area.

From Östersund, it’s a 45-minute bus ride to the project. We have been on plenty of site visits where the project could only be reached using 4x4s but in District Metals’ case, the company had organized a large touring bus to take all attendees to the project site. Not only was this useful to get a better understanding of the project and hear/see more details during the ride, it also is a testament to the quality of the existing infrastructure. There are very few projects in the world where you can drive up to outcropping mineralization using a tour bus. The pictures below and elsewhere in this report were taken while standing on one of the numerous outcrops of the alum shale mineralization looking down at the paved road winding through the property. And even when you turn off a paved road, a well-maintained gravel road takes you deeper into the core of the property. Access-wise it doesn’t get any better than this.

In fact, there are numerous existing paved and gravel roads throughout the property. This doesn’t have to be an issue as the region is very sparsely populated and traffic is very light. And if/when the property does get developed, the alum shale stretches out over several kilometers so we can imagine the operations would start in an area with the lowest disturbance.

Waiting for the uranium ban to be lifted

The explanation of the opportunity was thoroughly elaborated on by CEO Garrett Ainsworth and VP Exploration Hein Raat, but of course all eyes are on the Swedish government as the moratorium on mining and processing uranium is still in place.

While the executives of any company with uranium prospects in Sweden will undoubtedly be positive about seeing the moratorium getting lifted, it was good to hear ‘confirmation’ at the Nordic Funds & Mines conference in Stockholm. Maria Sunér, the CEO of SveMin, a pro-mining NGO, had a very strong opinion on the uranium moratorium. As you can see and hear below in the YouTube video, there were no ‘maybe’s’ or ‘eventually’s’. Her comment was that ‘The direction is very clear, they will lift the ban on [uranium] exploration and mining’.

The current ban on uranium mining in Sweden definitely is an issue for the Viken project, but it also creates a black-and-white situation. If the ban doesn’t get removed, the Viken asset is facing a tough time. But if it does get lifted, all uranium companies in Sweden will be on fire. And then District Metals’ Viken property with in excess of 1 billion pounds of uranium in the ground, could very well be the future of European uranium mining.

And that would make sense. France’s Orano, for instance, has been sourcing a substantial portion of its annual uranium needs from former colony Niger. After a coup d’état last year, and the new Niger government leaning closer to Russia, Orano was expropriated and lost its Niger-based uranium assets. It would only make sense if a large European producer of uranium is keeping European projects on its radar. It’s no secret French companies are heavily politicized and it was interesting to see president Macron visited Sweden twice in the very recent past. There were two official state visits, in October 2023 and January 2024.

Sweden could become Europe’s leading producer and provider of uranium, but for that to happen, lifting the uranium moratorium is a conditio sine qua non.

The potential prize? Let’s look at neighbour Aura Energy

We are arguing an investment in Swedish uranium assets still is a binary bet on lifting the moratorium. It will either happen, or it won’t. After our visit to Sweden and hearing the strong ‘on the record’ words from the CEO of SveMin, it sounds like the required radical change in perception of uranium and nuclear energy is actually happening.

In terms of a company being an interesting risk/reward proposal, District Metals’ risk is not a geological risk but a geopolitical risk: in order to unlock the full potential of Viken, the ban on uranium mining will have to be lifted.

But what about the other side of the equation? What about the reward?

A historical preliminary economic assessment published in 2014 confirmed the viability of the project. But truth be told, that PEA was focusing on a large scale operation running a 21 million tonnes per year operation that would cost US$1.23B to build. Those are 2014 dollars and after applying the impact of inflation, you can easily double that capex.

We would argue potential investors in District Metals shouldn’t really look at a 10 year old PEA which is based on a megalomanic project size with almost 100,000 tonnes per day in waste & rock mining. Also, this 2014 PEA did not include vanadium, molybdenum, or potash, which are critical in the potential value of these alum shale deposits. While low-grade projects like the Viken deposit definitely benefit from economies of scale, neighbour Aura Energy showed a better understanding of the metallurgical details of the alum shale, which showed miracles to the economics of the project.

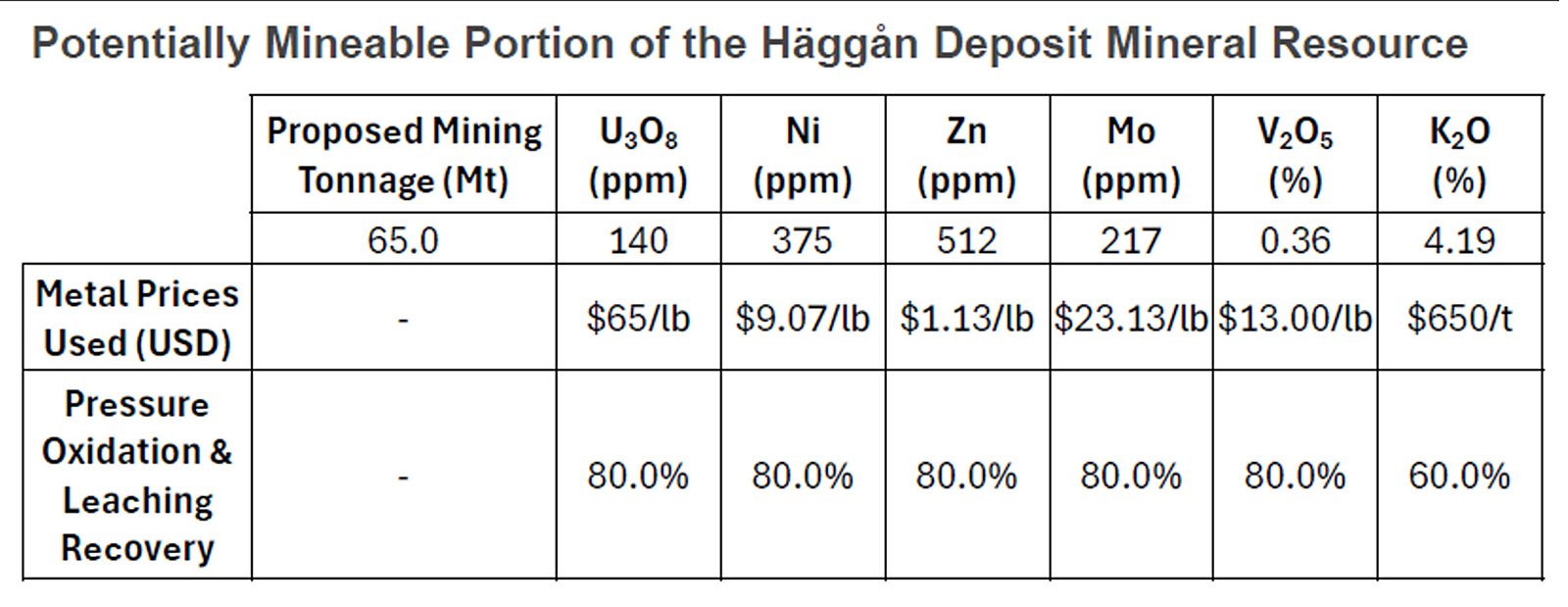

The September 2023 economics we will refer to below are related to Aura Energy’s Haggan deposit, which borders District Metals’ Viken deposit. Haggan basically is a continuation of the same alum shale mineralization so there shouldn’t be any meaningful discrepancies in grade, recovery rates and construction and operating expenses. The image below shows the initially planned 65 million tonne pit designed as part of the Haggan mine plan. And just to be clear: 65 million tonnes represents just 3% of the total Haggan resource which contains just over 2.0 billion tonnes, but the mine plan and economic scenario below is important to show smaller scale projects also work.

The main difference between the Haggan economic study and the 2014 Viken PEA? The input of vanadium, molybdenum and potash along with improved metallurgy. As shown above, Aura Energy expects to achieve an 80% recovery rate across the board for its main minerals, except for the potash production where a recovery rate of 60% is applied. The sole other difference in the Haggan study is that the historical Viken mine plan contained copper.

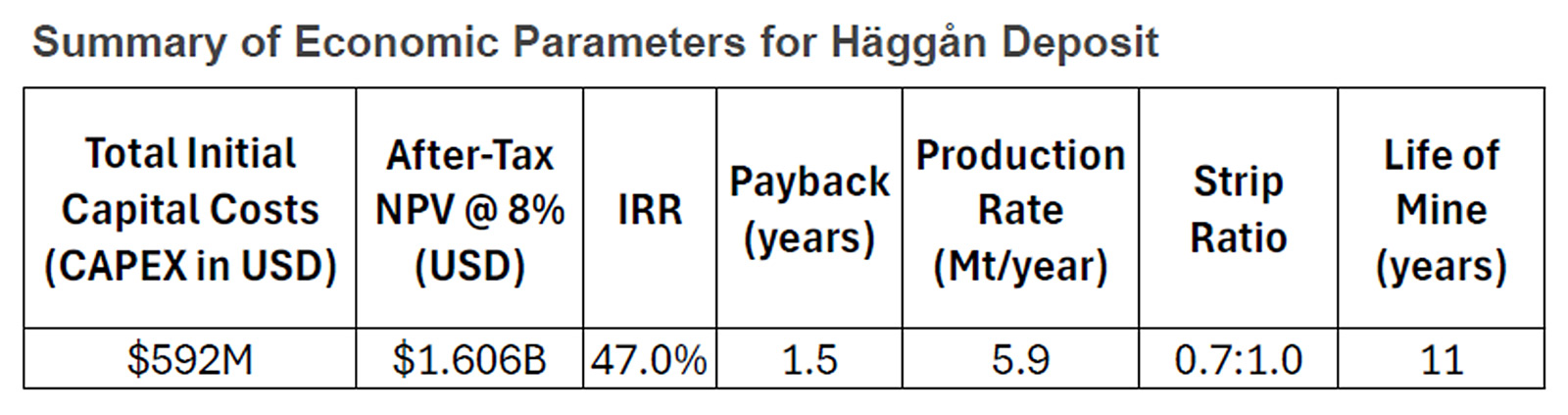

The Aura Energy study indicates the mine could get built for US$600M, resulting in an after-tax NPV8% of US$1.6B. That sounds phenomenal but let’s definitely not forget Aura’s vanadium price of 13 dollars per pound appears to be a bit optimistic considering the current world market price is less than half that number. On the other hand, the current uranium price is also substantially higher than the $65/pound used in the Haggan study.

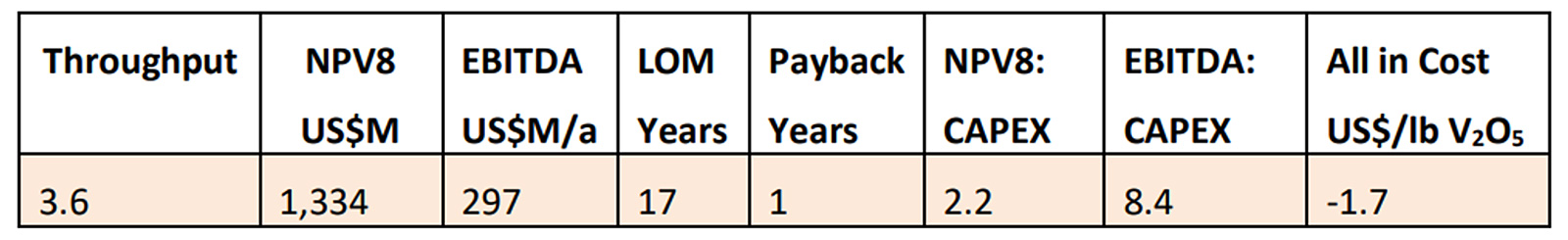

We pulled up the Haggan study to focus on the sensitivity analysis to make sure the higher uranium price could indeed compensate for the lower vanadium price. This is actually a bit complicated as Aura Energy’s base case scenario does not include the uranium as a by-product credit. However, the appendix to the scoping study includes a scenario where the uranium is mined, processed and sold at an average price of $65/pound. In that scenario, the uranium is considered a by-product of the polymetallic output. In Aura Energy’s case, including the uranium would reduce the AISC of vanadium to a negative $1.7 per pound.

This means that even at the current low V2O5 price of around US$4.60 per pound, the project would generate a net margin of $6.3 per produced pound, or $150M in annual net revenue.

Using an uranium price of $80/pound and a long-term vanadium price of $5.5/pound, the margin would increase to approximately $8.25 per pound as the higher uranium price would reduce the AISC per pound of vanadium to a negative $2.75.

Again, keep in mind the economic study is based on just 65 million tonnes of the currently known 2.0B+ tonnes resource estimate at Haggan. Once the processing plant has been built, Aura Energy can just continue to mine the alum shale.

Going back to District Metals (all numbers and results mentioned above are related to Aura Energy’s project, which we consider to be a very close comparable), it is clear the existing 3.0 billion tonnes historical resource estimate on the Viken project has the size of in excess of 40 Haggans studies. Additionally, should there ever be a need to add tonnage to the project, District can just continue to follow the alum shale in the north-northwestern direction where historical drill holes also intersected the mineralized alum shale, up to 10 kilometers north-northwest of the pit outlines in the historical 2014 Preliminary Economic Assessment. The question isn’t ‘is there more than 3.0 billion tonnes?’ but ‘How much more than 3.0 billion tonnes is there?’. But again, if the Aura Energy study is a blueprint for Viken, at a mining and processing rate of 6 million tonnes per year a resource expansion beyond 3 billion tonnes sounds like an issue for future generations to deal with.

Conclusion

While the Viken deposit could in theory be mined under the current rules and regulations, it would not be allowed to recover the uranium. In District Metals’ case, the uranium is important to the investment thesis as the economics of Viken would materially decrease without it.

This makes District Metals an intriguing bet on the Swedish government actually lifting the moratorium. The majority of the attendees and speakers at the Nordic Funds & Mines conference in Stockholm was pretty convinced the ban on uranium mining and processing will be lifted in the near future. And when that happens, we are convinced District Metals will have its day in the spotlights as the owner of an historical resource containing north of a billion pounds of uranium.

Disclosure: The author has a long position in District Metals. District Metals is a sponsor of the website. District Metals covered all travel expenses within Sweden. Please read our disclaimer.